Introduction

Over the last few years, the long term study of Aikido has been undeniably waning in popularity. A recent broad demographic study sponsored by Aikido Journal clearly shows that Aikido’s popularity is in decline. One of the major criticisms of Aikido is a lack of effectiveness as a martial art. Often, those criticizing Aikido online seem to have little actual experience outside of watching videos. The claimants often present an argument that there is no video evidence of Aikido being used in a “ring” or a “street fight”, and therefore, Aikido is ineffective. A lack of YouTube videos isn’t conclusive evidence of a lack of effectiveness. Street fighting and sports competitions are not the sole crucibles for determining martial effectiveness. The claim itself represents a logical fallacy. Additionally, lumping all Aikido practitioners into a single group, represents a gross generalization.

This being said, handwaiving dismissals of criticisms of Aikido are irresponsible. In my experience, some of the criticisms are valid. Critics claim that Aikido training uses unrealistic attacks. They also claim that techniques are practiced without “pressure”. The claim is also made that these training methods ultimately lead to a collusive relationship during training. Unfortunately, in many dojos, this isn’t too far off the mark. I’ve see this, and I’ve experienced it. Many dojos also seem proud to teach Aikido as some kind of “exercise system”, or as some form of “Japanese Yoga”.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I’ve spent some time wandering around the Internet looking at both videos and articles produced by other dojos. I’ve seen some really unusual Aikido. I’ve also read quite a few online articles that deeply mischaracterize Aikido. I recently stumbled upon a dojo web page that describes the Aikido that they teach as a using “dance-like moves”. They describe their practice as responding to “pretend” attackers by “spinning away” and “unbalancing” the attacker. Their description of Aikido also made the bold claim that there are no “punches or kicks” used in Aikido. This was followed by the claim that because there is no striking in Aikido, injury is very rare. These are startling statements. During a time when Aikido is clearly in decline, I think it’s time for some discussion about Aikido and martial effectiveness. Aikido is a martial art.

Dancing?

Aikido bears little resemblance to “dancing”. Aikido techniques, when executed correctly, are effective martial techniques. Every Aikido technique starts with taking an attacker’s balance (kuzushi). Kuzushi is followed by either throwing the attacker or “grounding” them by employing various pins and joint locks. These objectives aren’t consistent with “dancing”. This being said, I have visited a few dojos where the Aikido being practiced feels like some kind of “Japanese Yoga”. I’m pretty certain that this isn’t what Morihei Ueshiba O-Sensei intended when he created Aikido.

Speaking from my own experience, my Aikido studies have been pretty broad, with a strong focus on Iwama Aikido. I’ve never heard any of my teachers describe Aikido as being “dance-like”. My primary teachers are experts. In my opinion, the view that Aikido is, in any way, related to dance reveals a significant misunderstanding of Aikido technique. The only aspect of Aikido that is vaguely related to dance, is the requirement to maintain a connection with a partner. The analogy really starts and ends there.

I often wonder where the misconception that Aikido is related to “dance” comes from. This may have originated from a misinterpretation of a book authored by Terry Dobson Sensei. Unfortunately, I didn’t have the opportunity to spend any time with Dobson Sensei, but I know people that did, and I know people that knew him quite well. My understanding is that his Aikido was not at all like dancing. There is a good deal of video evidence available to indicate that this is the case. My understanding, as well, is that Dobson Sensei, later in life, came to regret having introduced the “dance” analogy.

Pretend Attacks?

Aikido training doesn’t use pretend attacks. Training in Kihon-Waza, or fundamental techniques, tends to use very clearly defined attacks, with well established protocols. These are basic attacks. The assumption that more advanced practice doesn’t include more advanced attacks is, in my experience, incorrect. Recently I’ve seen some discussion about Aikido attacks being representative of “sword attacks”. This is also incorrect. This seems to represent a deep misunderstanding of the Aiki-ken/Aiki-Jo/Taijutsu relationship.

The unfortunate truth, however, is that many Aikido students don’t seem to have ever been trained to attack properly. Many dojos seem to believe that proper attacks aren’t necessary. Students never learn more robust ukemi, and they and their training partners remain at a very basic practice level. Very little challenge is ever presented to either partner, outside of memorizing overly complex techniques. Students never learn to organize a response against more realistic attacks. There is never any risk of injury, and students are never able to refine their personal responses to escalated attacks. When training like this, the relationship between Uke (attacker) and Nage (defender) never progresses beyond a fundamental choreographed sequence.

The development of strong and increasingly realistic attacks represents an important component of Aikido training. An attacker (“Uke”) isn’t supposed to be a compliant rag-doll with limp and ineffective attacks that terminate as soon as technique begins. Uke’s training should include the development of strong attacks, with increasing resistance and a progressive increase in “aliveness”. As students progress, their ability to both attack effectively and apply Aikido technique efficiently and effectively is supposed to be progressive. This kind of training supports more advanced exploration of Oyo-waza (applied technique), and Kaeshi/Henka-waza (reversals/changing technique). It is almost impossible to practice effective oyo/henka-waza against poor and ineffective attacks.

No Striking or Kicking?

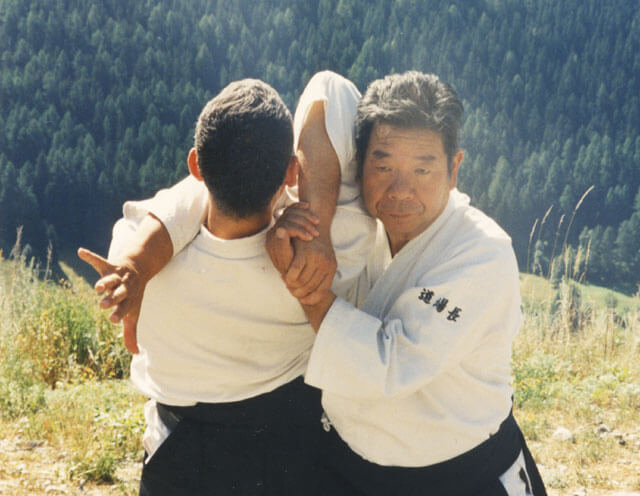

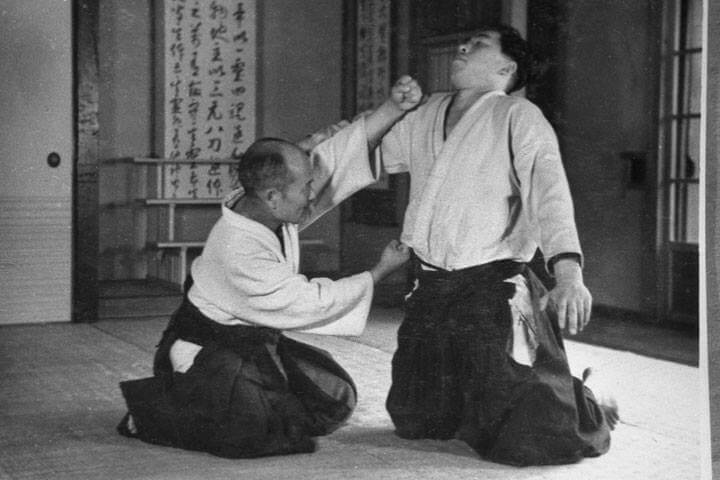

The claim that “punching/kicking” are not part of Aikido is a surprise to me. I’ve never trained in a style of Aikido that didn’t teach some form of atemi-waza (striking technique). Many Aikido techniques can’t be properly executed without an opening strike to begin the process of unbalancing uke. A large subset of Aikido techniques make no sense whatsoever without Atemi from the person doing the technique. Atemi is often used to gauge ma-ai (combative distance) during technique. On more than one occasion, Morihiro Saito Shihan pointed out that if you open with strong atemi, and the atemi hits the target, this might end the conflict without a need to escalate, thus re-establishing harmony efficiently and quickly.

“Atemi accounts for 99% of Aikido” was a remark once uttered by the Founder… However, there are quite a few cases in which the meaning of a technique becomes incomprehensible if the attendant Atemi is left out.

Morihiro Saito Sensei – Traditional Aikido Volume 5 (pg 38)

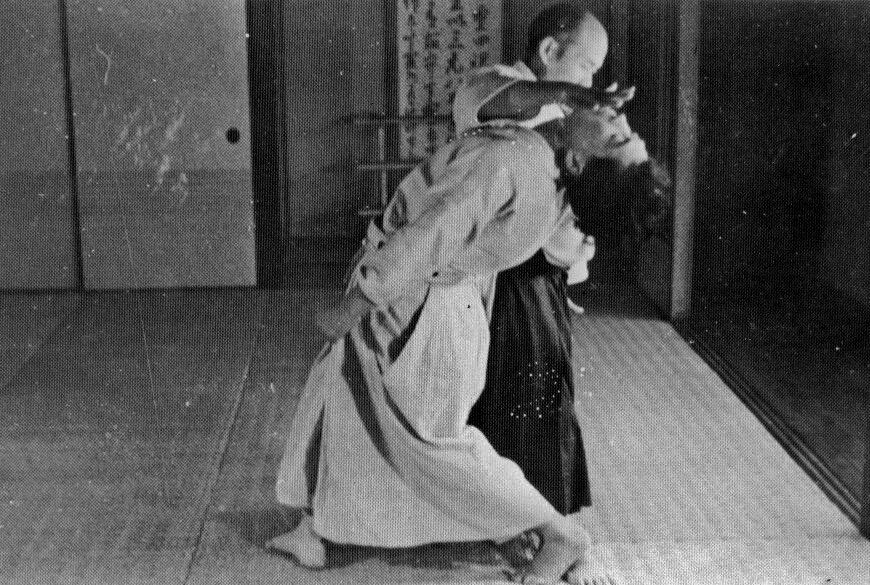

“Budo Renshu”, one of two books authored by Morihei Ueshiba O-Sensei, clearly indicates, in many of the photographs, the use of Atemi. The same is true in the drawings found in O-Sensei’s first book, authored in 1933, “Aikijujitsu Densho”. There are numerous videos of O-Sensei clearly making use of Atemi, even in demonstrations. O-Sensei obviously felt that Atemi was important.

Based on personal training experience, the application of Atemi, including, but not limited to open/closed hand strikes, elbow strikes, knee strikes, and low kicks are absolutely found in Aikido. Over the course of my Aikido career, I’ve both been taught a wide variety of Atemi, including kicks, and techniques to respond to “punches and kicks”. I cannot recall a single technique that doesn’t benefit from, or in many cases require Atemi. It is a bold and disinformed generalization to state that Aikido doesn’t include “punching and kicking”.

The exploitation of openings, or “suki”, is a major concept in the practice of Aikido. If students aren’t taught to make frequent use of Atemi, I don’t believe it’s ever possible to learn to recognize openings. Exploitation of an opening, if you don’t understand Ma-Ai (combative distance), and have no experience with Atemi, seems unlikely. It seems to me that training without Atemi is a lot like trying to learn to drive a car without ever starting the engine. Maybe you learn something, but I’m not sure anyone would call what you’re doing “driving”.

Low Risk of Injury?

I reminisced a bit about the risk of injury in Aikido being low. I’ve witnessed, or been party to, quite a few injuries on the mat. Most of the injuries happened after class during Jiyu Keiko (free practice). Over my 25+ years of practice, my personal injuries include, among others: A separated right shoulder, a rib broken out of my sternum, multiple bloody noses and black eyes, almost having had all of my front teeth knocked out at least three times, and numerous dislocated toes and fingers (mostly from dragging my feet on the mat). I’ve probably had multiple concussions and I’ve been unable, after particularly rough classes, to get up after laying down on my living room floor.

A spiral fracture of an Uke’s forearm is probably the worse injury I’ve witnessed. This happened during a Shodan test. We actually heard that injury before seeing it. Dojos ask people to sign injury waivers when they get on the mat because injuries do happen. We do everything we can to avoid injuring our partners, but it’s important to remember an adage that I’ve lived my life by since learning to sail in my early teens. “If you never capsize a boat, you’ve never actually sailed”. Injuries happen. If you’re actually practicing Aikido, and you’re doin’ it right, you’re going to at least occasionally catch a punch from uke.

What Really Contributes to Reduced Risk of Injury?

My views should not be interpreted, in any way, as a representation that careless practice is OK. I am, by no means, glorifying injury. Our training partners are giving their bodies to us to facilitate practice. It is everyone’s responsibility to absolutely respect the integrity of their partner’s body. But… The reality is that if you engage in anything more than the most basic practice, injuries do happen when pushing the training envelope. Every dojo that I’ve ever spent significant time in tends to be very careful about teaching effective ukemi (both attacking and receiving technique) and without exception, all of these dojos stand by the concept of TRAINING TO THE LEVEL OF YOUR PARTNER’S ABILITIES. I can’t count the number of times that I have heard my teachers say this. I remind my students of this continuously.

In my opinion, careful attention to ukemi, and making an effort to build an environment where students are careful with their partners are the predominant reasons why injuries are relatively rare during Aikido practice. As your training partners improve, so should you, and as you both improve the intensity of practice should also increase. Training should accommodate everyone. This doesn’t mean that the entire dojo should “train constantly to the lowest common denominator”. People have many different reasons for coming to the mat. A Dojo should do it’s best to accomodate these reasons, but in the end, compromising martial integrity should not be an option. Learning to execute technique along a broad spectrum of “power” is a principal goal in the practice of Aikido. Teaching ineffective technique does little to accomplish this. I do believe strongly that effective Aikido technique can be taught to anyone without regard for age, gender, or physical capability.

Collusive vs. Cooperative Training

It’s also really important to realize that Aikido isn’t unique in practicing cooperatively. I believe that Aikido does differ from many other martial arts in the maintenance of a careful balance between effective practice and the avoidance of “competition” between partners. Students have to learn sensitivity to their partner’s capabilities. They also have to dispense with their egos to the point that asking someone to “slow down” or “let up” becomes a comfortable request. This is at the heart of the difference between “collusive” and “cooperative” training. Cooperative training, targeting both continuous improvement and technical excellence, builds strong Aikido. Collusive training is a pointless waste of time and energy and has nothing to do with the path that O-Sensei left behind for us to follow.

I believe that a lack of competitive behavior on the mat is a major factor in reducing injury. Aikido doesn’t employ “pretend” attacks, nor do we eliminate striking. This is the harder road to take, and I believe far too many dojos perhaps don’t understand the importance of this balance. They either decide to practice in ways that don’t encourage growth, or they just never knew better to begin with. When you practice Aikido as some kind of dance, you get exactly what you bring to the mat. You end up with weak and ineffective technique. Students never come to understand Aikido as the Founder intended. Realizing “Takemusu Aikido” becomes an impossible goal.

Why am I Concerned?

I’ve devoted almost half my life to the study of Aikido. I’ve studied under some of the best teachers alive today. Many of my teachers are direct disciples of Morihiro Saito Shihan. Saito Sensei spent more time studying with O-Sensei than anyone else during O-Sensei’s lifetime. For the last three years, I’ve been running a dojo. I don’t consider myself an expert, but I do consider myself significantly invested.

Being frank, the martial integrity of Aikido is absolutely my business. After reading some of the posts I’ve seen over the last few months, and viewing some of the videos I’ve found online, I’ve never been more convinced to continue to make it my business. Aikido isn’t a hobby for me. Our dojo is not a business. For the first 18 or so years of my Aikido career, I was on the mat every week, between four and five times a week for multiple hours each class. I’ve traveled extensively to attend seminars across all major styles of Aikido. I still do. I maintain an active on-going student/teacher relationship with my teachers. The style of Aikido that I study was chosen carefully. The integrity of Aikido, both as a martial system, and as an art, is a deep and on-going personal concern.

Two Sides of a Coin… Harmony vs. Destruction…

A lot of Aikido’s often described benefits stem from the fact that it is a martial art. While a part of Aikido’s focus is on healing, and restoration of harmony, you cannot separate this “partition” from the other side of the Aikido coin. The ultimate purpose of any martial art is destruction. The view that Aikido, as created by Morihei Ueshiba O-Sensei, is a solely “defensive” art that involves “dance-like moves”, is incorrect. Aikido isn’t dancing. The people that train as if they’re training some form of “interpretive Japanese Yoga” that supports “self-expression” are not, in my opinion, training effectively. The idea that Aikido is anything like dance represents a misunderstanding of both the history and practice of Aikido.

My Aikido career started in the DC area, and I spent quite a bit of time practicing with direct students of Mitsugi Saotome Shihan. I have good deal of respect for Saotome Sensei, and his senior students. His views on the importance practicing Aikido as an effective martial art are quite clear. I present a quote from Saotome Sensei as someone outside of my direct lineage, as supporting evidence that these views are neither my unique views, nor are they unique to Iwama Aikido.

My purpose is to guide Aikido students away from the “dancing mindset’, from training in a comfortable way mentally and physically. I want to make them think about the real meaning, the real application of “harmony” – it comes from the moment of being in front of an enemy who can destroy you, who is not going to participate in your harmony. This is the essence of O Sensei’s Aikido meaning, and without this understanding Aikido is missing something important. I often ask my students, “can you defend your life?” Because if your answer is “no”, then your Aikido has no real meaning and you have no real understanding of Aikido principle. If Aikido is just dancing for you, then your Aikido is shallow, and it has no ability to either defend or heal.

Mitsugi Saotome Shihan

Similar quotes from direct students of O-Sensei (e.g. Morihiro Saito Sensei, Shoji Nishio Sensei, Kuzuo Chiba Sensei, and Gozo Shioda Sensei), can be found in open literature.

While Aikido’s practice and teaching methods are accommodating to people of all walks of life, in the end, O-Sensei intended Aikido to be a martial art. Martial integrity, and technical proficiency, are important and inseparable parts of the Art of Aikido. I deeply believe that long term dedicated practice of Aikido brings transformative benefit to people’s lives. I’ve seen it. I’ve experienced it. I also believe that if you pick and choose a “comfortable” path, you’ll never actually discover many of these benefits. Aikido is Budo. Nothing more. Nothing less.