Introduction

This is the second installment in a five post series discussing the role of “mindset” in serious Budo training. In a previous post, we discussed “Shoshin” (Beginner’s Mind). In this post, we take a look at “Zanshin” or “remaining mind”. One aspect of Budo training focuses on learning to live a life practicing an art that can potentially “take life” while simultaneously practicing to avoid doing so. The practice of Budo isn’t a religious pursuit. The aspects of mindset described in these posts are guideposts to the development of mindful behavior. The objective is to develop mindfulness that persists even under very stressful circumstances.

Our dojo doesn’t spend a lot of time discussing philosophy. The style of Aikido our dojo practices (Iwama-Ryu Aikido), believes that Aikido, including it’s philosophical foundation, is best learned through the practice of Aikido as an effective martial art. Aikido is Budo. We offer quite a lot of mat time during the week, but our practice time is still limited. Philosophical discussion is best left for after keiko.

Across this five post series, the various aspects of Budo mindset are presented without regard for order. They should all be developed in parallel as you continue forward in your studies. There is no specific order, or pre-requisites. All aspects of Budo mindset are equally important, and some are more difficult to develop than others. Life is short. Start immediately.

What is Zanshin?

Zanshin (残心), or “Remaining Mind”, is characterized as the state of being “connected” to an attacker. It is a state of sustained awareness of your entire environment, including any attackers. Zanshin persists before, during, and after the execution of technique. There is a strong sense of “follow through” associated with Zanshin as well. You achieve Zanshin when the mind is completely and effortlessly focused on the present action. The focus includes an awareness of your own mind, body, and surroundings. Zanshin, in daily life, manifests as living with purpose and intention rather than mindlessly living at the mercy of events.

Zanshin is, at it’s core, a state of sustained mindfulness. Practicing Zanshin during Aikido practice requires focus on “the moment” from the beginning of a specific practice to the end. As an example, you connect with your partner prior to an attack, activating a sense of mindful awareness of not just your partner, but the environment around you, your body, and anyone else that’s nearby. You maintain Zanshin throughout the technique, and then explicitly hold that awareness for short period of time after the technique is complete.

Continued serious practice of Zanshin on the mat leads to “anchoring” of the mind to experiences occurring in the present moment. The tendency of the mind to drift, during both day-to-day life, and under more extreme duress experienced during conflict is, over time, significantly reduced. You gradually lengthen the practice by maintaining focus during extended randori and jiyu-waza, eventually remaining in a state of relaxed vigilence. Zanshin is a natural state for humans. The practice isn’t so much about learning to DO something, it’s more about overcoming bad mental habits in order to maintain what is a natural state of mindfulness/connectedness.

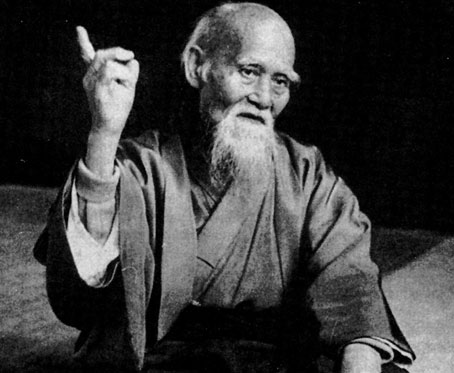

One of my sempai attributes an excellent description of the feeling of Zanshin to Morihiro Saito Sensei when he tells a story about Saito Sensei likening the feeling of Zanshin to “shooting a tiger”. One doesn’t shoot a tiger and then turn your back on it and absentmindely walk away. Aikido practice is in the same way. Saito Sensei regularly reminded people to “hold your form” at the end of execution of technique for two seconds as a basic Zanshin practice.

Always try to be in communion with heaven and earth; then the world will appear in its true light. Self-conceit will vanish, and you can blend with any attack.

— Morihei Ueshiba O-Sensei, The Art of Peace

Practicing/Applying Zanshin

The practice of Zanshin starts with adopting an attitude of serious practice on the mat. At the beginning of every encounter with your training partner, regardless of your role, you should begin the encounter by engaging a “soft focus” and connecting with your training partner. While some Aikidoka incorrectly view themselves as a “training dummy” when in the role of Uke, both partners should practice Zanshin. Throughout the execution of technique, remain connected to your partner. Focus on remaining aware of your own body and mind, and the environment around you (including those practicing nearby). When the technique completes, whether you are Uke or Nage, hold this state of mindfulness for two seconds after the technique finishes. When you first begin studying Zanshin, count “one… two…” silently, then gently let go of your focus and reset.

There is also a solo practice that you can use to help guide the development of Zanshin. Sit quietly near a tree. Look at the tree. Pick a single leaf and focus on that leaf. After a few minutes of focusing on that single leaf, soften your focus and look at the entire tree. After spending some time looking at the entire tree, work on seeing both the entire tree and all of the leaves. Don’t look at just the tree, or a single leaf. Look at the entire tree and try to see all the leaves in as much detail as you can.

End Notes

Zanshin is a fairly straightforward mindset to develop, however, it requires discipline both on and off the mat. Aikidoka should practice Zanshin regardless of their role during practice. This doubles your practice time and helps with rapid development of more effective ukemi. It is my opinion that development of Zanshin helps significantly both with identification of openings (suki) and with organizing and managing multiple attackers. The next mindset we’ll explore, in Part 3 of this series, is “Mushin” (無心), or “No Mind”.