Introduction

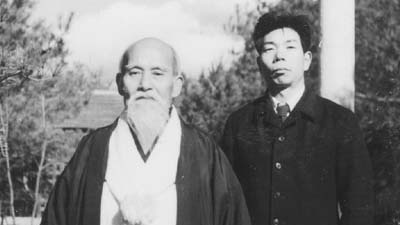

This is the first of multiple posts that are intended to help both me, and my students, develop a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the Iwama Ryu Aikido curriculum. Among a long list of other aspects, the well defined structure of the Iwama Curriculum has always appealed to the Engineer in me. This first post focuses on discussion of the different levels of Aikido practice, as originally defined by O’Sensei. Morihiro Saito Sensei also lectured about the various “levels” of practice at several seminars that were captured and distributed by Stan Pranin. While these posts represent notes, I’ll try to provide references where possible.

The Four Levels of Practice

The four levels of practice, as I understand them, are:

Kotai – Literal Translation “Solid (Body)”

Jutai – Literal Translation “Soft (Body)” (aka “Yawarakai”)

Ryutai – Literal Translation “Flowing (Body)”

Kitai – Literal Translation “Energy (Body)”

Sources vary a bit on the actual terms, and it can be a bit confusing that these are sometimes condensed into three levels (eliminating “Ryutai”). In some cases, a 5th level seems to be added, as well (“Ekitai”). “Ekitai” seems to represent a transitional level between Ryutai and Kitai. I’ve most commonly encountered the four levels outlined above, and it’s my understanding that these are the four levels that Morihiro Saito Shihan would typically lecture on. Let’s look at each level.

Kotai

Kotai is the most fundamental level of practice. This is often referred to as “static”, or Kihon, practice. Uke attacks with a very firm grab/realistic strike, and Nage responds with a strong/basic technique. The techniques are categorized as “Kihon-Waza” or “Fundamental” Techniques. Nage focuses on development of stable hanmi (stance), and a strong foundation. A strong center is developed, and practice focuses on basic angles and body mechanics. Iwama stylists focus principally on practice of Kihon Waza as part of the progression through the Kyu ranks. The Iwama taijutsu kihon-waza (“empty hand foundation techniques”) alone comprise more than 500 techniques.

At many dojos, students studying at this level are also exposed to the rich Iwama weapons curriculum. Early focus is on Ken/Jo suburi/awase, with progression to solo kata practice, advancing to paired practice using a “stop/start” approach. Ken and Jo-dori (sword and staff “taking”) and Jo-nage (throws with the staff), are also practiced.

Jutai

Jutai, often also referred to as “Yawarakai”, is the next level of practice. Nage begins to learn to adapt to stronger, less structured attacks, and basic “blending” practice begins. Some styles of Aikido begin by teaching at this level. I personally prefer the Iwama approach. I began my Aikido career at a Shin Shin Toitsu Aikido (Ki Society) dojo, and practiced there regularly for almost 5 years. While I understand an approach that starts with Jutai, I also see, and have directly experienced the benefits of training “kihon waza” as an Iwama stylist.

I was once advised by one of my Ki Society Sempai that Aikido is an “old man’s art”, and that one shouldn’t “use strength” during technique. Having had some experience with other martial arts, I found this statement confusing, and I didn’t really agree at the time. Now that I’m responsible for a dojo, and I’m teaching Aikido regularly, I still disagree, but for different reasons.

I think that it’s necessary to develop physical power/strength through repetition of Kihon-waza, and I think it’s necessary to continue developing that strength throughout your Aikido career. In parallel, I think it’s important to refine technique so that power becomes less necessary, but still available when required. The availability of power, in conjunction with refined technical skill, provides a wider “dynamic range” of possible responses. It is my opinion that the practice of Aikido without the development of strength, or power, becomes nothing more than the study of interpretive dance.

By the time a student reaches Shodan (1st degree black belt), he/she should be developing a more instinctual approach to Aikido. “Blending” with attacks should become more of a focus, with continued regular practice of kihon-waza. Techniques become more “resiliant”. I also believe that a consistent return to fundamental practice should be a constant thread in a student’s Aikido history.

Ryutai

Ryutai, sometimes referred to as “Ki-No-Nagare”. At this level of practice, techniques become more dynamic. Nage tries to develop more of a “sense” of Uke’s attacks. Nage begins to “flow” with Uke’s attacks, adapting when necessary to changing attacks. Ryutai Keiko (practice) is relatively advanced. This level of practice begins to develop significantly about the time the student achieves a rank of Sandan/Yondan (3rd/4th degree black belt).

Kitai

This level of practice requires decades of dedicated practice. The first three levels are, in many ways, considered “fundamental”. I don’t have much insight into this level of practice, as I sit firmly in the Kotai/Jutai realm at this point in my career (with, perhaps, the occasional accidental glimpse at Ryutai).

Conclusion

This blog post answers a question I’ve been asked a few times by my students. Future posts will address similar questions. My next post will focus on the naming of techniques and how techniques are categorized.